Recipe For Reflection: Transcriptions Give View Of Earlier Times

In the fragile pages of recipe books from the early modern period, UNC Charlotte researcher Jennifer Munroe and her students find traces of life and death.

They decipher the words and absorb the daily struggles and joys of the women who created these chronicles of life between 1550 and 1800. These books are much more than repositories for recipes.

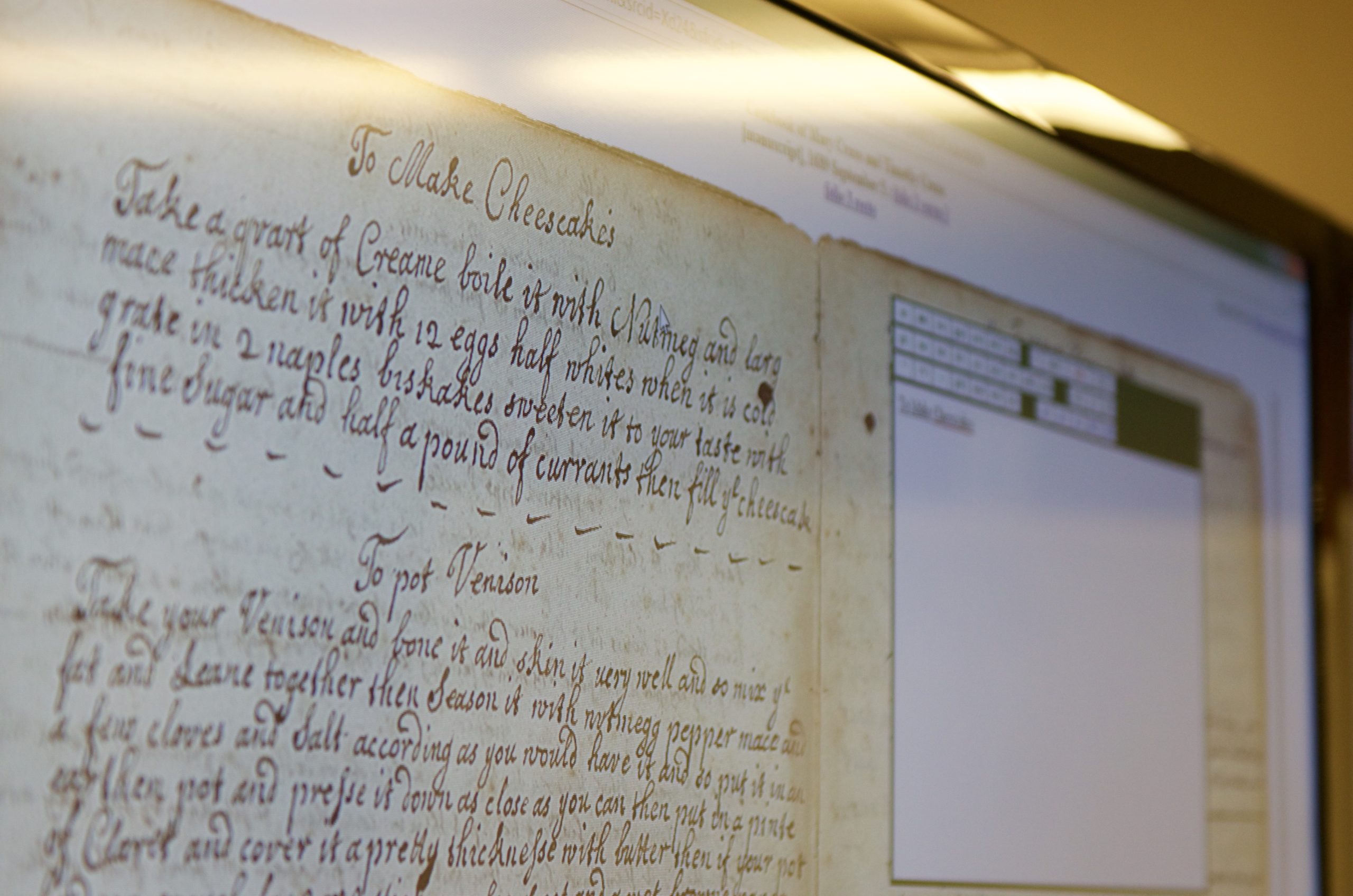

“Imagine a handwritten recipe book from, say, 1615,” says English graduate student Robin Kello. “It contains various recipes for food, remedies for varied maladies, maybe notes from a sermon, doodles, or astrological advice about unlucky days. Plum wine, pudding, gall stones, insomnia, frenzy or madness, we have found all of this between the pages of a bound, handwritten volume.”

The books were seldom if ever published. They were private documents, used in women’s households and by groups of women. Until recently, these voices have been silenced in the quiet, dusty stacks of far-flung libraries or tucked away in the basements of farmhouses in the English countryside.

With advances in technology, scholars can find new audiences for these women’s thoughts and their ways of life. Through the process of transcription, scholars worldwide are digitizing images of each page of old books, transcribing the vocabulary and script and publishing the content in online databases for the world to study and share.

Giving Women A Voice

“It’s important to give these early modern women a voice,” says English graduate student Breanne Weber. “Western culture is really beginning to return to nature, as we realize now how much has been lost as we’ve become more industrialized. The women – and men, but mostly women – who kept these recipe books exemplify that connection to the earth that we as a society have been missing. It’s almost like validation that our ‘back to nature’ movement is legitimate. We’re just longing for something fulfilling that we’ve had in the past.”

As an associate professor in the Department of English, Munroe’s research focuses on the intersection of ecological and feminist theory in literature. She has written or co-edited five books and teaches courses in early modern English poetry and prose, Shakespeare, ecocriticism, gender studies, literary theory and film.

“Including manuscript documents in our collective research and teaching gives us a way to uncover experiences and perspectives that previously were marginalized,” Munroe says. “We find new ways to think about questions of feminism and ecofeminism, related to the women’s relationship in particular with the nonhuman world.”

When using recipes as texts in her classes, Munroe and her students consider what the documents reveal about early modern women’s domestic work, the differences between amateur and professional labor, the way in which these are views untouched by government propaganda, the historical context of early modern science and practices related to what we call “sustainability” today.

When using recipes as texts in her classes, Munroe and her students consider what the documents reveal about early modern women’s domestic work, the differences between amateur and professional labor, the way in which these are views untouched by government propaganda, the historical context of early modern science and practices related to what we call “sustainability” today.

“Transcribing helps us understand sustainability as relates to these women, thinking about their environment and how they used the plants and animals around them,” Munroe says. “They were connected in ways we are disconnected, because they knew where their medicine and food came from.”

Teaching Students How To Approach Texts

Munroe uses recipes as one tool to help students learn new ways to approach texts. The handwritten documents, with their unfamiliar words, spellings and construction, require the reader to read differently. Because they were texts to be used in the kitchen work, they do not follow a conventional, linear narrative. To grasp the meaning completely, the reader must move back and forth through the text more than once and adapt to what was not said, to know what constitutes a “soft fire” or “take when ready.” This non-linear approach can be applied to other texts, yielding new skills and knowledge.

One of Munroe’s goals is to facilitate greater sensitivity to relational thinking, such as how neglecting a fundamental connection to the nonhuman things that surround us can lead to problems, such as environmental destruction and climate change.

One of Munroe’s goals is to facilitate greater sensitivity to relational thinking, such as how neglecting a fundamental connection to the nonhuman things that surround us can lead to problems, such as environmental destruction and climate change.

To learn more and to build connections within the field of paleography, or transcription, Munroe and four graduate students traveled to the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C. in fall 2015 for a transcribathon. Over 90 students and scholars who were gathered at the library and connected digitally around the globe spent 12 hours transcribing all 200 pages of a recipe manuscript in the Folger’s collection.

“The transcribathon at the Folger Shakespeare Library was incredible,” Weber says. “We were there with some of the most prominent scholars in their respective fields and were warmly welcomed as equal partners in the communal project of transcribing the late 17th century recipe book of Rebeckah Winche.”

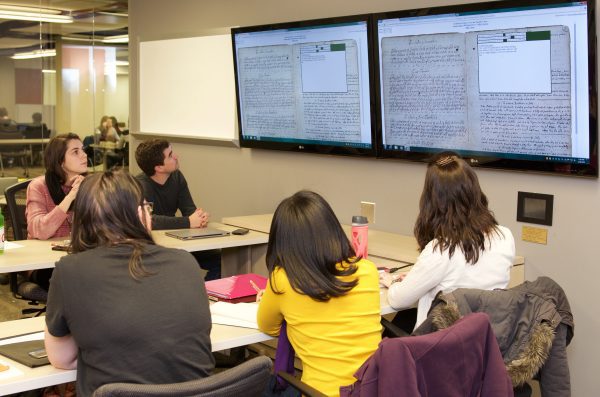

“Our intention is to share the amazing experience of transcription, everything from frustrations to triumphs, with others, and build our own transcription community on the campus of UNC Charlotte,” Weber says. “At our meetings, we project pages from early modern recipe books onto a screen and work as a group to transcribe into the Folger Shakespeare Library’s database, where our transcriptions will be accessible to the public at some point.”

The society hosted its first transcribathon at UNC Charlotte in early April. Over 7 students, faculty and alumni from UNC Charlotte and other campuses across the country transcribed an anonymous c. 1720 English cookbook. Members of a roundtable talked about growing herbs, cooking, transcription, digital humanities work and other research, and the connection to sustainability. Attendees sampled Angelica candied using a 17th century recipe, found in a manuscript and made by EMPS members from plants grown by the UNC Charlotte Botanical Gardens staff.

As UNC Charlotte continues to grow its research and teaching in this digital humanities area, those involved are focusing on the breadth of what these books say.

“This cutting-edge research is wide-ranging and interdisciplinary,” Kello says. “A student of history, literature, anthropology, political science, environmental science, or any interested party can look into these books and see how larger cultural ideas about food and medicine were changing, how increased transnational trade provided different commodities to middle class English families of the 17th century, how folk knowledge was passed on and interpreted before the standardization of medicine, how the English language has changed, or – not to be too much of a nerd – find a recipe for cheesecake that goes back four centuries.”

Words: Brittany Algiere and Lynn Roberson | Images: Lynn Roberson