Paper Trails: Author Traces Family’s Journey Through Time

The soldier’s face has faded in the World War II photograph, falling victim to the ravages of time. Yet, even as the picture has turned cloudy, the image of her father has grown sharper in Barbara Presnell’s mind.

Presnell, an award-winning documentary poet and essayist, has captured the story of her father William G. Presnell in her Blue Star collection, published earlier this year by Press 53 in Winston-Salem.

The poems trace over a century in the life of her family, with a focus on their connection to wars from the Civil War forward. She has found the stories in family memories, military records, census reports, letters, journals, maps, medals, and over 3,000 photographs she found in dusty boxes in the attic.

Barbara Presnell

“I don’t think this is a pro-war book. I don’t think this is an anti-war book. I think it’s a factual book about war being part of our lives,” says Presnell, a senior lecturer with the University Writing Program.

At its root, Blue Star is more about family than war. It documents one family’s journey through time and tragedy, offering a backdrop that lends a raw and intimate grace to the moments of tenderness throughout.

When her father enlisted in the National Guard in 1940, he was 24 years old. Four years later, he was called to active duty in Europe as a member of the 120th regiment of the 30th Infantry Division. Following his discharge, he returned to his North Carolina hometown to raise a family and make his living in textiles.

The recipient of two Purple Hearts and survivor of the Normandy Invasion and the Battle of the Bulge, he died following routine surgery at age 52. Presnell was just 14 years old.

She and her siblings were left with little understanding of his earlier life, including his time during the war and its impact on him. As children, they had paid scant attention to his stories. Following his death, their mother discouraged lingering in the past.

“I now wanted to try to understand who my father was,” she says. “I searched for answers to my most important questions. I wanted to know who was my father as a boy? How did his childhood shape him into the young man who went off to war? How did war shape him into the father I knew?”

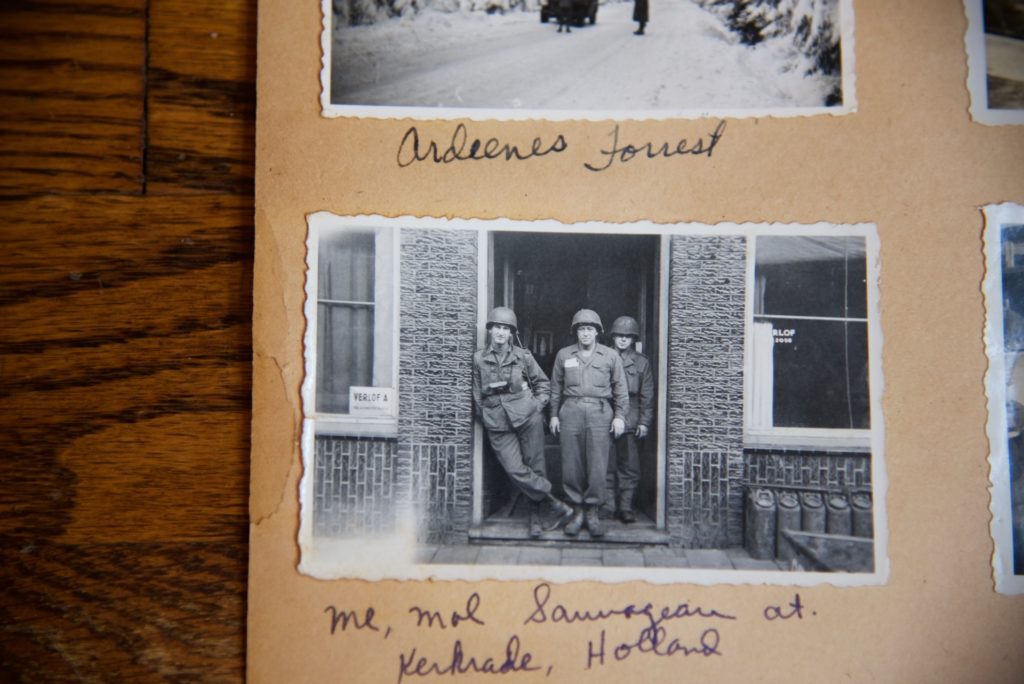

William G. Presnell (left) with his trusty camera around his neck.

Presnell began writing the poems in 2012, in an effort to answer her lingering questions through her inquiry-driven poetry. She pieced together the factual foundation over time.

One interesting find came when a cousin was cleaning out her house and found books with Presnell’s father’s name scrawled in them.

“There’s this one book, an eighth grade French textbook,” Presnell says. “He was just as bored as he could be, and he had actually carved the title out of this book and rewritten it as How to Cuss in French. Well, how ironic that he ends up in France able to speak the language. Looking back, here is a kid in eighth grade without any foresight, without any thought that he’s going to be in France in ten years, with his life on the line.”

During her exploration, Presnell turned to her father’s dusty boxes of memorabilia. The cartons had traveled to Presnell’s house from the family homeplace following her mother’s death. There, the boxes waited, tucked away until the day Presnell opened the first box and sifted through its contents.

It became clear that Presnell’s father, in his role as first sergeant, must have served as an official record-keeper for his regiment. The few photographs of him show his trusty camera slung around his neck.

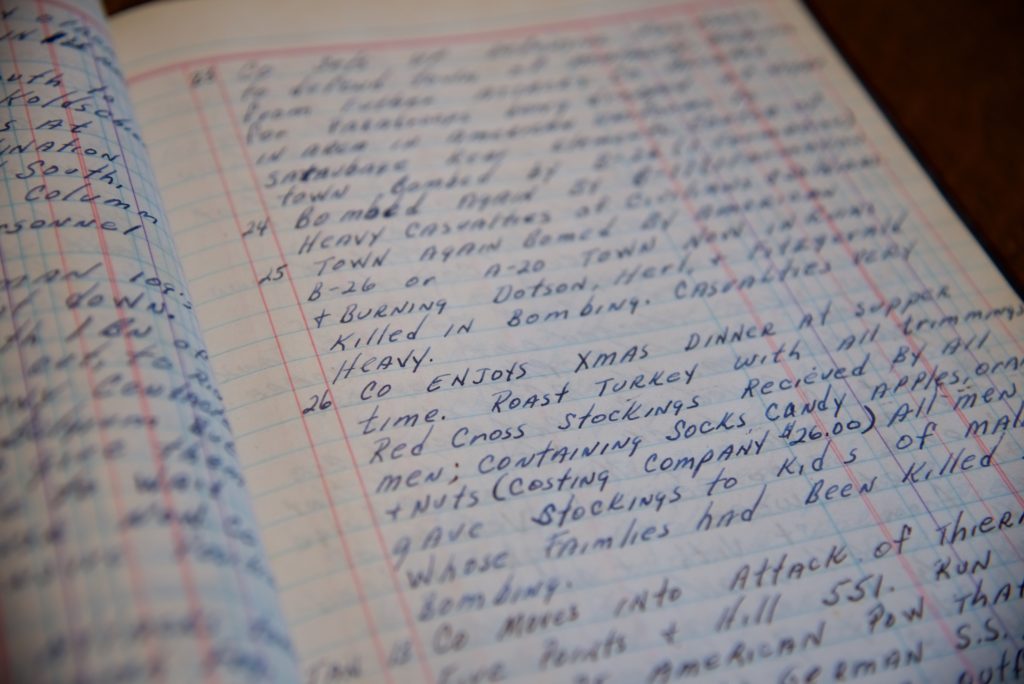

He, on the other hand, wrote thousands of journal entries and took thousands of photographs, an unusually large number in the days of film. He meticulously documented the activities of his fellow soldiers and townspeople. The images show work details and slices of life – soldiers with their arms around young women, rolling cigarettes, lining up for chow or the latrines.

He, on the other hand, wrote thousands of journal entries and took thousands of photographs, an unusually large number in the days of film. He meticulously documented the activities of his fellow soldiers and townspeople. The images show work details and slices of life – soldiers with their arms around young women, rolling cigarettes, lining up for chow or the latrines.

He also took ground and aerial views of the terrain, bridges, roads and towns. Orchards, livestock, and bombed out buildings appear in other photographs.

“He was charged with keeping records of all the men and what happened to them,” Presnell says. “We have a journal of their movement through Europe. We have 3,000 photographs, two scrapbooks, and lots and lots of stuff that documents their travels. My brother and sister and I decided that we would follow that trail, and along the way, try to find people we could talk to about it.”

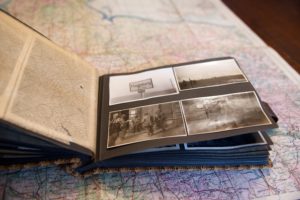

In 2014, Presnell, her husband, her siblings and her sister’s husband acted on that decision, setting out to trace the journey through France, Belgium, The Netherlands, and Germany. They plotted their trip using her father’s map, marked by his hand with a path from Omaha Beach in Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge to the end of the war in the European Theater in late April 1945.

In 2014, Presnell, her husband, her siblings and her sister’s husband acted on that decision, setting out to trace the journey through France, Belgium, The Netherlands, and Germany. They plotted their trip using her father’s map, marked by his hand with a path from Omaha Beach in Normandy to the Battle of the Bulge to the end of the war in the European Theater in late April 1945.

Photographs pasted into scrapbooks with legends aided their journey, as did phone calls and emails to find contacts in the area.

During their 21-day trek, they found many of the spots her father had documented in his journal, including the 12th century Rolduc Abbey in the Netherlands, where the troops rested between battles. The abbey, now a convention center, offered them a place of respite as well.

The mayor of Mortain, France hosted a reception for the family, as he does for all returning veterans and their families. They met historians and people who were liberated as children during the war and who expressed gratitude to Presnell’s family, as Americans.

“We don’t even understand how much the soldiers did,” she says. “My appreciation for that has greatly increased since I was over there and studied closely what they did, walked through their trail. But for the most part, we just don’t think about that. And it’s cliché, but it’s so true, we’re here because they were there.”

They stood on the very spot on the banks of the Elbe River in Magdeburg, Germany where a rare photograph of her father shows him standing between two Russian soldiers. In the picture, he drapes his arms loosely over the Russians’ shoulders, the stub of a cigar gripped between two fingers and smiles on the three faces. It is April 25, 1945, the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, marking an important step toward the end of the war.

They stood on the very spot on the banks of the Elbe River in Magdeburg, Germany where a rare photograph of her father shows him standing between two Russian soldiers. In the picture, he drapes his arms loosely over the Russians’ shoulders, the stub of a cigar gripped between two fingers and smiles on the three faces. It is April 25, 1945, the day Soviet and American troops met at the Elbe River, marking an important step toward the end of the war.

This precious image came to her from Frank Towers, a veteran she found who remembered her father and wrote, “I think I have a picture of your father with some Russian soldiers.”

In “The Dance,” Presnell speaks of finding her father’s spirit in this place where “you are a boy my son’s age.”

Poems in the collection also talk of the connections between mothers and sons, including Presnell’s with her own son. She details Quaker roots and Native American heritage, as well as World War I connections.

While she worked on Blue Star, Presnell found that the work of her students in her classrooms became richer and more authentic as a result of working alongside one another and sharing in common journeys. “We had our exciting finds and frustrating dead ends,” she says.

“My students have recovered lost Civil War ancestors, traced immigration journeys, uncovered Holocaust stories, and confirmed and refuted long-told family legends of all kinds,” she says.

“One young man investigated his grandmother’s death in a helicopter crash during the Vietnam War, while another dug into newspaper accounts from the 1970s to learn about his uncle’s involvement in gay rights in New York City,” she says. “A young woman explored her grandfather’s association with the Italian mafia. There are so many more examples, each one its own fascinating tale.”

Through her own family-based inquiry project, Presnell has helped her students understand that research and writing are about seeking answers to questions that grow and change along the way.

For her, the Blue Star journey has brought greater understanding of her family and of herself. By “putting the family story into a shape that’s going to be passed down to the next generation,” as she describes it, Presnell has perhaps become a reflection of her father, the record-keeper.

Words: Brittany Stone | Images: Lynn Roberson