The Grove: Sacred Grove Reveals New View of Africa’s Past

Surrounded by the sprawl of a modern city, the dense forest grove of Osun-Osogbo in southwestern Nigeria has long stood as a silent sentry guarding the mysteries of the ancient past. Those secrets are now revealed by UNC Charlotte researcher Akin Ogundiran, whose work has upended long-held views of how West Africa became a global economic player.

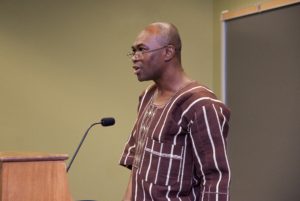

Ogundiran, chair of the Africana Studies Department and professor of Africana studies, anthropology and history at UNC Charlotte, has spent years sifting through the soil of Osun-Osogbo.

His research is proving that Africa – long thought to be a mere supplier of raw materials and labor to a world considered more civilized – was actually a significant manufacturing pioneer with finished goods eagerly sought by European traders.

His research is proving that Africa – long thought to be a mere supplier of raw materials and labor to a world considered more civilized – was actually a significant manufacturing pioneer with finished goods eagerly sought by European traders.

“Many scholars of the previous generation already made up their mind that it was not possible for African cultures to develop iron production on their own, to build cities on their own,” Ogundiran says. “Africa was coming out of colonialism in the 1960s, so the kind of historical view that was created at that time tended to denigrate past achievement.”

As a young boy growing up in Nigeria, Ogundiran had heard the narrative that was long accepted. As the widely held story goes, African communities knew how to trade, but had not created technologies and products on their own.

A critical focus for his research was how the Yoruba people of West Africa became part of the global economy.

“It’s a big question,” he says. “Societies that were autonomous, with their own traditions, own economic systems and own way of life – when and how did they become part of wider economic networks?”

Researchers had probed the question before, but mostly focused on the Atlantic coast and the contact the Yoruba had with Europeans. “I’m saying, ‘No, no – the coast was actually just a point of exchange,” he says. “The goods were coming from the mainland. That was the center of the action.”

To unearth clues to Nigeria’s precolonial economy, Ogundiran needed a piece of ground that had escaped the rapid development of much of his home country, land that had somehow been sealed off from development for more than a thousand years. That search led him to Osun-Osogbo.

To unearth clues to Nigeria’s precolonial economy, Ogundiran needed a piece of ground that had escaped the rapid development of much of his home country, land that had somehow been sealed off from development for more than a thousand years. That search led him to Osun-Osogbo.

Local people had for centuries set aside the sacred grove for the worship of the Yoruba goddess, Osun. A UNESCO World Heritage site, the grove has been preserved for its religious and cultural importance. Long before the 75-acre forest was a place of worship, it was the site of a thriving village, and residents left behind fragments of their economic life.

Permission secured to do his work, Ogundiran and his team began digging. They unearthed pottery, terracotta figure, brass jewelry, and cowrie shells once used as currency. As Ogundiran peeled back years through layers of soil, he found artifacts dating from the busy trading years of 1575 to 1720. He found pipes modeled after prototypes from Florida, which were used to smoke tobacco imported from Brazil.

While all these finds proved significant, the most exciting finds were broken pieces of glass.

While all these finds proved significant, the most exciting finds were broken pieces of glass.

“These were not just glass beads,” Ogundiran says. “We also found glass waste products and raw materials, indicating there must have been some glassmaking industry around that area. We began to see glass-making crucibles.”

Historians had long considered African glass-making a kind of recycling. The common thinking was that Africans imported glass from the Mediterranean and melted it to make beads. That type of glass was typically fragile, crumbling to dust if not preserved. Ogundiran’s glass was rock-hard.

“I thought, ‘This cannot be Roman or Islamic glass,’” he says.

In 2011, he called in a geochemist colleague to analyze the glass he had found. The results shocked them both. The Yoruba glass was not simply remade from imported Islamic, Roman or Chinese glass. It was fortified with a granitic material that made it unusually strong, and it was an original product.

“It shows that as early as about 1100 AD, they were making glass products,” he says. “When the Portuguese and Dutch arrived on the coast of West Africa, they did not have sufficient products of their own that people desired.”

What people wanted was Yoruba-made glass. Tinted into lush blues and greens with the addition of cobalt and magnesium, the glass was a desired commodity, moving from manufacturing sites in the heartland to the European traders’ hands on the Atlantic coast. Europeans plied these beads to different African nations along the coast.

Sculptures in the Grove

Ogundiran’s research at Osun-Osogbo revealed the early peoples of his homeland were much more than middlemen. He and a colleague published their findings in the Journal of Black Studies.

“Glass-making is one of the tests of a really great civilization,” Ogundiran says. “This is changing the narrative of Africa as a continent just supplying raw materials.” The complexities of turning a composition of different minerals into highly specialized, very hard and brightly ornamental glass signal the existence of protected intellectual property, he says.

Ogundiran has received support from the Social Science Research Council, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, National Endowment for the Humanities, Dumbarton Oaks, The Carnegie Foundation, and the National Humanities Center, among others, to further his research.

He is widening his focus to other parts of the Yoruba region, studying how people managed to thrive in places where the environment is highly challenging.

“I’m now asking questions regarding the environment and social resilience, how societies built cities as a way of creating resilient adaptations,” he says.

Ogundiran plans a book that will describe the history of the grove from 1575 to present, with a focus on how to protect what is special about the place even as the city surrounding it grows.

Protecting the land is crucial, he says, for its biodiversity and also for its archaeological secrets that only now are being revealed.

Words: Amber Veverka | Images: Courtesy of Akin Ogundiran and Lynn Roberson