Consuming Identity: Research Finds Role of Food in Redefining the South

Pull it from the oven, crisp, golden and fragrant in its cast iron pan. Slather the top with melting butter, drizzle on the honey. That wedge of hot cornbread is more than just lunch. It’s a statement – about you, your family and perhaps about the place you occupy in the story of the American South.

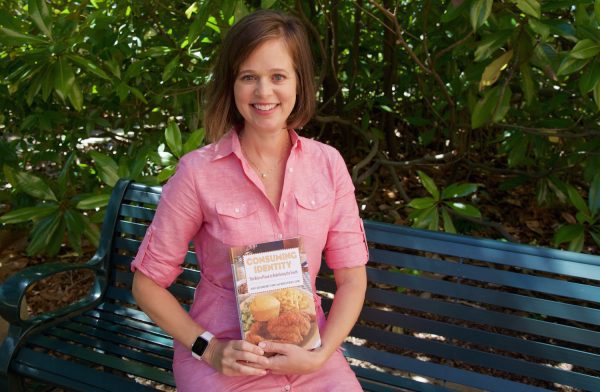

On a journey through the restaurants and kitchens of the South, the linkage between food and identity came clear to Ashli Quesinberry Stokes, a communication studies associate professor and director of the Center for the Study of the New South. She and her colleague, Wendy Atkins-Sayre, faculty at the University of Southern Mississippi, have co-authored a compelling book that details their findings.

Consuming Identity: The Role of Food in Redefining the South (University Press of Mississippi), documents how food flavors our memories and messages, telling stories both intentional and unintentional.

Stokes presents her book and the “story behind the story” at Personally Speaking on Tuesday, Sept. 26, 2017 at UNC Charlotte Center City (320 E. 9th St., Charlotte 28202). This is the first of the 2017-18 Personally Speaking series which features faculty from UNC Charlotte’s College of Liberal Arts & Sciences discussing their books and how they came to write them.

“A lot of people are writing and talking about Southern food,” Stokes says. “What we have done is write about the way people are talking about Southern food. When we in communication studies use the word ‘rhetoric,’ we’re talking about persuasion and persuasive messages. We were interested in how the messages we send about food – by talking about it or serving a particular food – shape who we are.”

“A lot of people are writing and talking about Southern food,” Stokes says. “What we have done is write about the way people are talking about Southern food. When we in communication studies use the word ‘rhetoric,’ we’re talking about persuasion and persuasive messages. We were interested in how the messages we send about food – by talking about it or serving a particular food – shape who we are.”

Food tours throughout the South took the researchers to farmers markets, restaurants, gas stations, and home kitchens. Stokes and Atkins-Sayre ate, asked questions and listened as the people they met served up story after story.

“We call it rhetorical field research,” Stokes says. “There has been a movement in my field to get beyond just what’s on the page. I’m a rhetorician by training, and I usually study words on a page. This time, we were studying persuasion by having conversations, analyzing photographs on restaurant walls, tuning into the music playing in the background, and even considering the neighborhood we’re exploring.”

Their research builds upon the argument that food holds such significance to Southern culture that it can also offer a way to help build connections across lines of class and race.

“Southern food and Southern food movement rhetoric serve a constitutive, or identity-building, function by helping to craft a Southern identity based on diverse, humble, and hospitable roots,” they write. “This identity offers a hopeful alternative to those identities based on race and class divisions and regional stereotypes. Moreover, this constitutive work has the potential to open up dialogues in the South and create communities by considering the diversity of experience through the celebration of the food.”

Stokes says the research indicates that one reason so many are drawn to the Southern table is that the foods of the region help create a sense of “us-ness” among those that pull up a chair. Or, said another way: Barbecue.

“Someone might write about fried chicken or other popular Southern entrees, but when she declares a style the ‘right’ kind of barbecue, she immediately speaks to her background, upbringing, and expectations,” Stokes writes. “Tussling about which barbecue is best engages identity-forming behavior.”

Barbecue is a shared love, even with its stark divisions. Despite brightly drawn lines – the red sauce fanatics, the vinegar aficionados, the mustard-lovers all standing well apart from one another – barbecue still serves as a bridge across cultural lines. Barbecue joints draw fans from all backgrounds, to eat their style of choice side by side, often tightly packed in at egalitarian counters.

“Food can’t fix everything. But maybe you can start a conversation because of a dish you have in common,” Stokes says. “What does this mean in this weighty, divisive time? To me, it symbolizes an opening. Not a fix. But maybe an opening.”

Stokes previously has researched and written about public relations and social movements. She found herself drawn to the Slow Food movement and decided with Atkins-Sayre to meld the interests. They read everything they could on Southern food, and compiled lists of the foods they thought would be represented by different regions of the South.

Stokes previously has researched and written about public relations and social movements. She found herself drawn to the Slow Food movement and decided with Atkins-Sayre to meld the interests. They read everything they could on Southern food, and compiled lists of the foods they thought would be represented by different regions of the South.

Then it was time to hit the road, with their questions and their appetites.

At low country Bowens Island Restaurant near Charleston, S.C., they joined locals and island guests gathered around as a heap of steamed oysters poured onto raw, pinewood boards. The authors learned how best to pry open the shells and delved into coastal history, joining in fellowship forged around the communal table.

At Doe’s Eat Place in Greenville, Mississippi, the conversation was bathed in hospitality, as the owners pressed on the researchers sample after sample of all the meats on the menu. At Domilise’s sandwich shop in New Orleans, they listened to guests and servers discuss the recent death of the restaurant’s matriarch, and the place she held in history.

Food tells stories of death, but also of birth, background and belief. Consider the humble cornbread, about which fierce opinions fly. Should it contain white cornmeal or yellow? And, most contentiously, does sugar belong? Respected food writer Kathleen Purvis explored the sugar-in-cornbread debate in a newspaper story that generated some of the hottest debate of anything she has written. It turned out people were worked up not about a recipe, but about an implication that the way you like your cornbread depends on your family’s racial and economic roots.

A preference for sweetened cornbread historically may have spoken “to whether you had the ability to afford sugar or the type of cornmeal you were using,” Stokes says. “If you had sugar, you could sweeten yellow cornmeal a bit.”

The research comes at a time of national fascination with authenticity in flavors, ingredients and meals. Purvis, who is food editor for The Charlotte Observer and author of books on Southern ingredients, says the pull toward Southern food is an old one, in part because of the messages many believe Southern food sends.

“There’s something about a lot of it that is a romanticized notion about the South being a simpler, ‘truer’ place,” she says. “I think that’s what people are drawn to.” For Stokes and her colleague, the draw remains a desire to uncover the deeper message.

Words: Amber Veverka | Images: Lynn Roberson